By Sheila Kieran

From its earliest days, Canadian governments were determined to control women’s reproduction. In fact, even before it was a country, its constituent parts had passed laws that took decisions about having children away from women. By 1892, when John Thompson was Prime Minister, the first Criminal Code prohibited abortion and, at the same time, forbade the sale, distribution, and advertisements of devices of contraception. Between 1926 and 1947, 4,000 to 6,000 women died as the result of illegal abortions. (And, of course, the number is almost certainly much higher, given society’s disapproval of the procedure.)

In 1968, Dr. Henry Morgentaler began performing illegal abortions in his private Montreal clinic as a matter of conscience, to help save women’s lives. Morgentaler was an early advocate for reproductive health, providing his patients with contraceptives and family planning advice, and he argued before the House of Commons that the current abortion laws were threatening the lives and safety of women.

During this time, McGill students Donna Cherniak and Allan Feingold of the McGill Student Society in Montreal produced and published Canada’s first handbook on contraception, before distributing such information was legal. The “Birth Control Handbook” went on to become an underground bestseller and was later translated into French. The students also circulated information about abortion, including how to do self-abortions.

It was not until 1969 that Parliament, by a vote of 149 to 55, amended the Criminal Code to permit abortion under certain limited circumstances. The legislation also permitted contraception and legalized homosexuality. The bill allowed hospitals to set up “therapeutic abortion committees” of three doctors to approve abortions if the woman’s life or health is at risk. The new arrangement was the result of pressure mostly from doctors and lawyers and medical groups. It seems that a few hospitals in big cities were already approving abortions by committee in order to reduce the risk of prosecution of any one doctor. That process became codified in law to benefit doctors, not women.

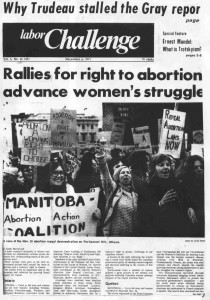

It was not until the law passed that the women’s movement in Canada woke up and began agitating for their rights, starting with abortion rights. In the spring of 1970, an Abortion Caravan of women started out from Vancouver and arrived in Ottawa two weeks later to protest the law. . Led by Vancouver activists such as Betsy Wood, Marcy Cohen, Ellen Woodsworth, and Margo Dunn, the Caravaners promptly staged a series of meetings and demonstrations that culminated on Mother’s Day when a group of women chained themselves to the parliamentary gallery in the House of Commons. Nineteen days later, Trudeau attended a press conference where, if he hoped to win women over, he failed spectacularly when Women’s Caucus members accused him of being unconcerned about the needs of poor women who couldn’t afford termination procedures. The next day, Dr. Henry Morgentaler, a survivor of Hitler’s death camps, was arrested at his Montreal clinic and charged with two counts of conspiracy to perform abortions. In January of the next year, a further charge was laid against him.

By 1973, although anti-choice groups had presented a petition with more than 350,000 signatures (and later, a petition with a million signers), the inevitable move to freedom of choice was well underway. Despite repeated and increasingly spiteful attempts to jail Dr. Morgentaler and his associates, including Dr.Yvan Macchabee, juries persisted in acquitting them. The following year was marked by the creation of the Canadian Association for the Repeal of the Abortion Law (later called the Canadian Abortion Rights Action League – CARAL). In December 1975, the newly elected Quebec Liberal government dropped all charges against Dr. Morgentaler and declared Canada’s abortion law unworkable.

However, attempts to jail them were not the most dangerous problems faced by doctors and their colleagues – not just Dr. Morgentaler, but also Dr. Robert Scott, Maria Corsillo, Dr. Leslie Smoling, Dr. Nikki Colodny, Joanne Cornax, Lynn Crocker, and Quebec doctors Dr.Yvan Macchabee, Jean-Denis Berbube, and Simon Tanguay. As anti-choice crusaders dealt with defeat after defeat, they became increasingly desperate and found themselves aligned with people willing to turn to life-threatening violence. Perhaps encouraged by governments’ unrelenting harassment of men and women involved in the pro-choice movement, they began to trade their failed arguments for weapons and bombs. In June 1983, a man tried to attack Dr. Morgentaler with gardening shears outside of his Toronto clinic. The doctor was saved from harm when friend and supporter Judy Rebick pushed the assailant away. The following month, a fire was set in the Women’s Bookstore in Toronto, which shared a building with the Morgentaler Clinic. The clinic suffered smoke and water damage, but fortunately no one was present at the time. Then in early 1991, youths set fire to a gasoline-soaked tire and hauled it onto the porch of the clinic, where it caused $7,000 worth of damage. (A few days earlier, a woman had released butyric acid – a so-called “stink bomb – in the clinic’s washroom).

In September of 1975, the Badgley Committee was established to study, among other issues, the way the Canada’s abortion law operated. Two years later, the Committee’s report concluded that the law discriminated against poor and rural women and that “health” was interpreted arbitrarily – a serious problem in legislation centred on the health of the mother.

It must have also amazed some Canadians that same year to discover that, in Criminal Code cases, the courts could reverse jury verdicts, as one court had with Dr. Morgentaler. In July, an amendment to the Code (known as the Morgentaler amendment) ended that possibility. Meanwhile however, Dr. Morgentaler was still in jail after being previously given an 18-month sentence for performing abortions. He was finally freed in January 1976 after serving 10 months. While in solitary confinement, he suffered a mild heart attack and was transferred to a convalescent home. (It’s hard to imagine the effects of such confinement on a survivor of Hitler’s death camps, but if the government thought that would deter Henry Morgentaler from his life’s work, they clearly didn’t know their man.)

Anti-choice activists started trying to undermine Therapeutic Abortion Committees (TACs) at hospitals in the late 1970s and continuing up to 1987. They took to running for hospital boards in cities across the country in an effort to elect majority anti-choice boards. If they won, the new board could be counted upon to disband the TAC or staff it with anti-choice doctors. At some of those painful and protracted hospital board elections, thousands attended to vote one way or the other. Sometimes the anti-choice side won, sometimes the pro-choice side won.

The late ’70s and early ’80s continued the pattern of raids on Morgentaler facilities, court charges, and jury acquittals. In Manitoba in 1985, and for three years thereafter, Dr. Morgentaler was forced to stop performing abortions because of police raids and the resulting inability to find doctors willing to carry out the procedure.

Throughout this time, the pro-choice movement grew in strength and numbers. Pioneering activists like June Callwood, Judy Rebick, Norma Scarborough, Carolyn Egan, Ruth Miller, Cherie MacDonald, Ellen Kruger, and many others supported Dr. Morgentaler in his battles, but they also worked tirelessly to build the women’s movement, improve access, and destigmatize abortion.

On January 28, 1988, the Supreme Court of Canada, led by Chief Justice Brian Dickson, struck down the abortion law in a 5-2 decision. The court found the law unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated Section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms by infringing on a woman’s right to life, liberty, and security of the person. It is this decision that we now celebrate.

Historical Archive Articles

- “Why Abortion Should be Legalized in Canada” by Dr. Benjamin Schlesinger. July, 1962. Liberty Magazine.

- “How the Hospitals Broke the Great Abortion Silence” by Walter Stewart. May 6, 1967. SW Magazine.

- Women’s Caucus of Vancouver letter to Prime Minister Trudeau demanding repeal of abortion law (.pdf). March 19, 1970.

- “Abortion Law ‘a Farce’” by Kayce White. January, 1975. Vancouver Sun.

- “One Man’s 16-Year Crusade”. April 7, 1985. Vancouver Province.