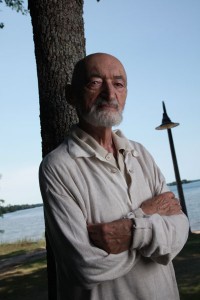

Henry Morgentaler. Photo credit: David Eisenberg.

Henry Morgentaler: A Timeline Biography

KEY DATES

1923 — Henry Morgentaler born in Lodz, Poland.

1950 — Moves to Canada after surviving Holocaust.

1955 — Starts a family practice in Montreal.

1967 — Urges Commons committee to reconsider abortion law.

1969 — Opens Montreal abortion clinic.

1974 — Acquitted by Quebec jury, later overturned by Quebec Court of Appeal. A jury later acquits Morgentaler a second time.

1984 — Acquitted by Ontario jury on abortion charges along with two other doctors.

1988 — Hails Supreme Court of Canada ruling striking down the abortion law as unconstitutional.

2005 — Receives honorary degree from the University of Western Ontario in London.

2008 — Named to the Order of Canada.

2013 — Dr. Morgentaler’s 90th birthday, and his death.

Henry Morgentaler was born in 1923 in Lodz, a large Polish city near the German border. When Germans invaded Lodz during the Second World War, his father was arrested and murdered by the Gestapo. Henry and his family had to move into the Lodz Ghetto, a district created for Jews and sealed off. Henry was 16 at the time, and tried to escape to Warsaw with some friends but was caught and returned to Lodz. His sister did escape with her boyfriend to Warsaw but ended up in the Warsaw Ghetto and later perished in the gas chambers at Treblinka. At the Lodz Ghetto, education was forbidden but Henry became an underground teacher of young students.

Four years later, the Lodz Ghetto was liquidated. Those who had managed to survive the acute deprivations without succumbing to disease or suicide, and had not already been transported in cattle cars to death camps, were sent to concentration camps. Henry, his brother Mike, and their mother were put in a transport to Auschwitz where selections were swiftly made for slave labour camps or gas chambers. Their mother was directed to the left; Henry and Mike to the right. From there, the two brothers were transported to Dachau labour sub-camps in the countryside: the ration for the day was one watery bowl of soup. Mike, small and wiry, stole potato peals from the garbage to share with Henry.

Henry and his first wife, Chava Rosenfarb, were high school sweethearts in Lodz prior to the war. She was transported to and then liberated from the Bergen Belsen Concentration camp. They were reunited after the war. Henry stayed in Germany on an American scholarship for his first year in university. Chava left for Belgium where Henry joined her a year later and continued his University courses in French. They married in 1949 and emigrated to Canada a year later. Chava was a poet, and her talent was discovered by the Montreal Jewish Public Library. She received help to come to Canada, and Henry came with her, completing his medical degree in French at the University of Montreal. In 1955, he opened a family practice in a house in the east end of Montreal where he built a clientele of working class people. He was one of the first Canadian doctors to perform vasectomies, insert IUDs, and provide contraceptive pills to the unmarried.

In 1967, Dr. Morgentaler presented a brief before a House of Commons Health and Welfare Committee that was investigating the problem of illegal abortion. Morgentaler stated that any woman should have the right to end her pregnancy without risking death. The reaction to his public testimony surprised him: he began to receive calls from women who wanted abortions. At the time, attempting to induce an abortion was a crime punishable by life in prison, and two years’ imprisonment for the woman herself. Dr. Morgentaler at first refused requests to end pregnancies, referring to two other physicians providing abortions, until his conscience overcame his fear.

In 1968, Dr. Morgentaler founded the Montreal Morgentaler Clinic, the first freestanding clinic to offer safe abortion services in Canada. It was established when Dr. Morgentaler, as an activist with the Canadian Humanist Association, began protesting Canada’s restrictive laws. The clinic was situated in the same house where Dr. Morgentaler had his family medicine practice, and remained there until 1995.

In 1969, the federal government amended the 1869 law that made abortions illegal in Canada. Abortion became legal under restricted conditions. It could be performed if a 3-doctor hospital committee decided that continuing the pregnancy would likely endanger the woman’s life or health. Morgentaler’s abortions remained illegal under that new law because he did not submit them in advance to a “Therapeutic Abortion Committee” for approval, and they were not done in hospitals.

In 1970, Dr. Morgentaler’s Montreal clinic was raided by police and he was charged with performing illegal abortions. In 1971, he was again charged in Montreal with performing an illegal abortion.

In 1973, Dr. Morgentaler issued a public statement that he was providing abortions. In May, he demonstrated his technique by performing an abortion on national television. Dr. Morgentaler estimated he had provided 5,000 safe abortions by that time. The Montreal clinic was raided again and ten new charges were laid. In November, a jury acquitted Dr. Morgentaler.

In 1973, Morgentaler was one of the signers of the second Humanist Manifesto, which set out updated tenants of the Humanism’s values and ideals.

In 1974, the Court of Appeal reversed the 1973 acquittal, and Dr. Morgentaler appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada. Mr. Justice J.K. Hugessen sentenced Dr. Morgentaler to 18 months. He remained free pending his appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

In March 1975, the Supreme Court dismissed the appeal. Dr. Morgentaler served 10 months in Montreal’s Bordeaux jail, where he suffered a mild heart attack. In June, a jury acquitted Dr. Morgentaler on a second count.

In 1975, the American Humanist Association named Dr. Morgentaler “Humanist of the Year.”

In 1976, the Court of Appeals denied the Crown’s appeal of Dr. Morgentaler’s June 1975 acquittal and the Supreme Court of Canada let that denial stand. The federal government amended the Criminal Code to prevent any future appeal court ordering conviction after jury acquittal, called “The Morgentaler Amendment”. The Minister of Justice set aside Dr. Morgentaler’s 1974 conviction and ordered a new trial. Dr. Morgentaler was released from custody. The new trial resulted again in acquittal. In November, the newly elected Parti Québécois government announced that outstanding charges against Dr. Morgentaler would not proceed and that doctors providing abortions in Quebec would not be prosecuted.

On June 15, 1983, Dr. Morgentaler opened an abortion clinic in Toronto, Ontario. By this point, abortion was the most controversial issue in the country.

In 1983, Dr. Morgentaler opened a clinic in Winnipeg. The clinic was raided and Dr. Morgentaler, Dr. Robert Scott, and head nurse Lynn Crocker were charged with procuring a miscarriage. Police also raided the Toronto clinic, seizing equipment and charging Drs. Morgentaler, Scott and Smoling with conspiracy to procure a miscarriage. The defence filed a motion challenging the constitutional validity of s. 251 of the Criminal Code. The Toronto clinic also suffered an arson attack.

In 1984, the judge dismissed the defence motion challenging the constitutional validity of s. 251, but the jury acquitted all three doctors. The Ontario Attorney-General appealed the acquittal. The Toronto clinic reopened, and Ontario filed new charges against Drs. Scott and Morgentaler.

In 1984, Dr. Morgentaler is also the subject of a National Film Board of Canada documentary Democracy on Trial: The Morgentaler Affair, directed by Paul Cowan.

In 1985, two more raids on the Winnipeg clinic resulted in six additional counts against Dr. Morgentaler, bringing the total number of charges outstanding against him in Manitoba to seven. The Ontario Court of Appeals set aside the Toronto jury’s acquittal and ordered a new trial. Dr. Morgentaler appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada.

In 1986, Toronto police laid charges against Dr. Morgentaler, Dr. Scott, and Dr. Colodny, but the Attorney-General stayed the proceedings pending the Supreme Court of Canada appeal. The Manitoba College of Physicians and Surgeons rejected Dr. Morgentaler’s request for a license for his Winnipeg clinic on the grounds that the Criminal Code states abortions can be performed only in accredited hospitals.

In 1987, Dr. Morgentaler was scheduled for arraignment on charges initiated by ex-boxer and anti-choice advocate Reggie Chartrand. Dr. Morgentaler petitioned Quebec Superior Court to block all actions against him by anti-abortion people. The court eventually ruled that two complaints against Dr. Morgentaler by Chartrand were valid and that a pre-inquiry should determine if there were grounds for formal charges against the doctor. Dr. Morgentaler’s arraignment on the charges was postponed pending the Supreme Court of Canada ruling on his case in Ontario. Meanwhile, the Ontario government dropped the 1986 charges against Drs. Morgentaler, Scott and Colodny.

In 1988, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down Canada’s abortion law (section 251 of the Criminal Code), ruling that it conflicted with rights guaranteed in the Charter. The Justices found that the law violated Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms because it infringed upon a woman’s right to “life, liberty and security of the person.” The decision came approximately 20 years after Dr. Morgentaler first performed an abortion. The federal government introduced a resolution to Parliament containing the broad outline of a new gestation-based abortion law. The resolution was defeated, along with five amendments. Abortion is now like any other medical procedure, governed by the Canada Health Act.

In 1989, the province of Nova Scotia passed legislation prohibiting the performance of abortions in clinics, in response to Dr. Morgentaler’s plans to open a free-standing abortion clinic in Halifax. The Canadian Abortion Rights Action League (CARAL) launched a legal challenge of the Nova Scotia legislation, but were denied standing by the Nova Scotia Supreme Court. Dr. Morgentaler challenged the law by announcing that he had just performed seven abortions at his Halifax clinic. He was immediately charged under the provincial Medical Services Act. After seven additional charges were filed, the province obtained an injunction against his performing any more until charges against him had been heard.

In 1990, a Nova Scotia provincial court judge struck down the Medical Services Act as unconstitutional and acquitted Dr. Morgentaler of all charges. The court found that abortion law is a matter of federal, not provincial jurisdiction. The Nova Scotia government appealed this decision.

In 1992, a firebomb destroyed the Toronto Morgentaler Clinic.

In 1993, the appeal division of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia upheld the lower court decision in favour of Dr. Morgentaler. The Nova Scotia government appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada, which dismissed the appeal, thereby confirming that the province was improperly trying to legislate in the area of federal criminal law.

In 1994, Dr. Morgentaler opened an abortion clinic in Fredericton, New Brunswick. The NB government invoked its Medical Services Payment Act, which prohibited doctors from performing abortions outside an approved medical facility. The NB College of Physicians and Surgeons restricted Dr. Morgentaler’s license to practice and he stopped offering abortion services. The New Brunswick Court of Queen’s Bench ruled that the province had no right to restrict abortions to hospitals, and that its medical legislation overstepped the legitimate powers of a province. New Brunswick appealed.

In 1997, Dr. Morgentaler challenged a PEI regulation that denied payment under the province’s health care plan for an abortion unless it is deemed medically necessary and performed in a hospital. The court ruled in favour of the government.

In 2002, Dr. Morgentaler wrote new federal Minister of Health Anne McLellan, urging her to force Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Manitoba and PEI to fund abortions in clinics. Dr. Morgentaler also announced his plan to sue the Manitoba government for not funding his clinic. Doctors Henry Morgentaler and Claude Paquin, two of the founding members of the Association for Access to Abortion, announced that the Association was filing a motion alleging that the Government of Quebec had intentionally violated the Health Insurance Act. The AAA asked the government to reimburse women who had had to pay for an abortion, a claim that amounted to tens of millions of dollars. Dr. Morgentaler announced plans to sue the New Brunswick and Nova Scotia governments for not funding clinic abortions.

In 2003, Dr. Morgentaler sued New Brunswick for its refusal to fund clinic abortions. New Brunswick Justice Minister Brad Green vowed to defend the province’s decision not to fund clinic abortions, stating the province was willing to take the issue to the Supreme Court of Canada. Dr. Morgentaler closed his Halifax clinic, stating that women in Nova Scotia could now get appropriate care at the QE II Health Sciences Centre, thanks to a physician providing abortions there whom Dr. Morgentaler had trained.

In March 2005, the University of Western Ontario (in London) announced that an honorary degree would be conferred on Morgentaler, the first time he would be given this honour. Opponents gathered 12,000 signatures on a petition, while a counter-petition of support for Morgentaler collected 10,000 names. An anonymous donor withdrew a promise of a $2 million bequest to the university, but another donor contributed $10,000 and the university president said other cheques had flowed in from supporters. In a speech at the ceremony, Morgentaler described his struggle to make abortion legal, available and safe in Canada, and expressed surprise at the “hullabaloo” over Western’s decision.

In 2005, the CTV television network produced a television movie documenting Morgentaler’s life and practice called Choice: The Henry Morgentaler Story.

On August 5, 2005 Morgentaler received the Couchiching Award for Public Policy Leadership for his efforts on behalf of women’s rights and reproductive health issues. The Award was given by the Couchiching Institute on Public Affairs at its 74th annual summer conference. In part, the citation reads:

The women’s movement of the 1960s found in Dr. Morgentaler a person who understood that women’s equality could not be achieved within the existing restrictions on medical services for reproductive choice. In offering women access to necessary services that faced considerable restriction elsewhere, Dr. Morgentaler used both his professional status and personal skills to fight for women’s rights, while placing himself at risk. His actions have brought about fundamental changes in Canadian law and to the health care system and in so doing dramatically affected for the better the lives of Canadians from coast to coast.

In 2006, Morgentaler had to stop performing abortions after undergoing a heart bypass surgery. However, he continued to oversee the operation of his six private clinics.

In May 2008, the Canadian Labour Congress recognized Dr. Morgentaler with its highest honour, the Award for Outstanding Service to Humanity.

On July 1, 2008, Dr. Morgentaler was appointed to the Order of Canada for his commitment to increased health care options for women. The anti-choice community protested strongly, but a national public opinion poll reported that two-thirds of Canadians supported Dr. Morgentaler receiving Canada’s highest honour.

In 2008, the New Brunswick courts granted Dr. Henry Morgentaler public-interest standing to challenge the constitutional validity of the province’s ban on payment for abortions at clinics. The province had asserted that Morgentaler did not have standing to bring the action but the judge stated that Morgentaler was “a suitable alternative person” to bring an action that women seeking abortions would be reluctant to undertake. The province appealed the court’s decision.

In 2009, the Appeals Court of New Brunswick upheld the lower court’s decision that Dr. Henry Morgentaler can sue the Government of New Brunswick to fund abortions at his clinic in Fredericton.

In 2010, Henry Morgentaler was nominated for a Transformational Canadians award as a person who has “made a difference by immeasurably improving the lives of others.”

March 19, 2013: Dr. Morgentaler celebrated his 90th birthday.

May 29, 2013: Dr. Henry Morgentaler dies peacefully at home, reportedly due to heart problems.

(Thanks to Gertrude Katz for offering some corrections to the early history in this article; revised July 15, 2016)